Tech has been through a rocky patch so far this year, what with the gyrations of the stock market, delayed IPOs, depressed valuations, renegotiated term sheets, and layoffs. How does this align with what we’re seeing on the ground in the tech and venture ecosystem in Southeast Asia?

Our observations in the first half of the year are that investors continued to bankroll their fundraising activities and pressed on with new and follow-on investments into Southeast Asian startups despite current market conditions. Surprisingly, as at the date of this report, the pace of investments coupled with ever-growing deal sizes suggest an inverse correlation to the market correction.

For example, three Genesis portfolio companies announced strong follow-on Series C rounds in the first half of 2022, registering between a 1.78x to 2.92x increase in their enterprise value. In April, Sequoia-backed Trusting Social, an impact-driven Fintech focused on creating unique, personalised financial credit scores for the unbanked and underbanked individuals, announced its initial close of $65 million led by Vietnam’s consumer-focused conglomerate Masan Group.

A month later, Believe, a direct-to-consumer (D2C) startup specialising in consumer beauty products and backed by Accel India, raised a $55 million Series C financing led by Venturi Partners. In June, Deliveree closed its $70 million Series C led by Gobi Partners and SPIL Ventures (the CVC arm of Salam Pacific Indonesia Lines). Deliveree has been focused on creating a dynamic marketplace for the trucking industry across Indonesia, Vietnam and Philippines, matching independent truck drivers and customers with cargo.

And this was on the back of various other deals announced publicly. Indonesia’s Fintech Flip raised $100 million Series B (Tencent, Block, Insight); eFishery $100 million Series C (Temasek, Softbank, Sequoia);, Bibit $80 million (GIC); Astro $60 million Series B (Accel, Tiger Global); Singapore’s ShopBack $80 million Series C (Asia Partners); BioFourmis $300 million Series D achieving unicorn status (General Atlantic); Neobank Stashfin $270 million equity/debt Series C (Uncorrelated Ventures); Neuron Mobility $43 million Series B (GSR Ventures, Square Peg); Multiplier $60 million Series B (Tiger Global, Sequoia); Thailand’s Fresket Series B $23 million (PTT Oil, Openspace) and many more.

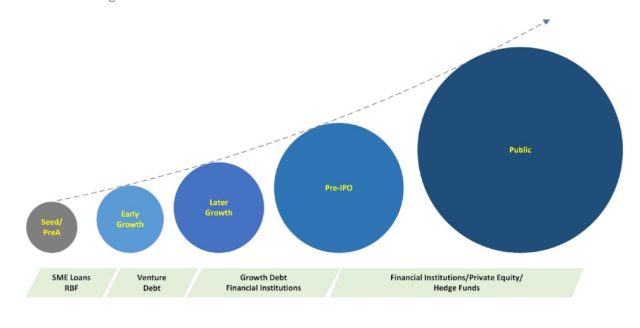

We also observed a continuation of Seed and Series A funding closes for startups across Southeast Asia. For example, Eratani, an Indonesia-based agritech startup raised a $1.6 million Seed round while Li Ka-Shing’s Horizons Ventures co-invested $7.5 million into Ilectra Motor Group, a 2-wheeler EV targeting the Indonesian market.

A Return to Profitability With Leaner Companies

Growth, especially growth at all costs, requires significant capital to take market share now and worry about profitability later. More often than not, customers and revenue acquired in such fashion are far from ideal, leading to higher churn rates, lower retention rates, and driving up costs even further. Raising too much capital at early stages can result in undisciplined spending leading to layoffs and other painful reactions when the burn rate skyrockets and future funding becomes scarce.

It is sobering to see news on startup layoffs across US and Asia including Southeast Asia (here are some dedicated websites tracking these statistics) and casualties such as Kaodim, an 8-year-old startup in Malaysia, which means “take care of it”, that shuttered its services as Covid halted the home-services industry. Softbank Asia’s Propzy, which bagged a $25 million Series A in 2020, dissolved a major part ofits business and reportedly laid off 50% of its employees.

On the flipside, good founders understand the value of a long-term mindset and the importance of building startups with the right values and structure so they can grow into lasting companies. The “exuberant climate” for start-ups has turned and investors are demanding to see financial metrics that are in line with the company’s stage of development. Therefore, it is prudent for start-up leaders to make adjustments in order to enhance operational efficiency and to focus funding resources to achieve important key performance indicators so as to reach the next funding round.

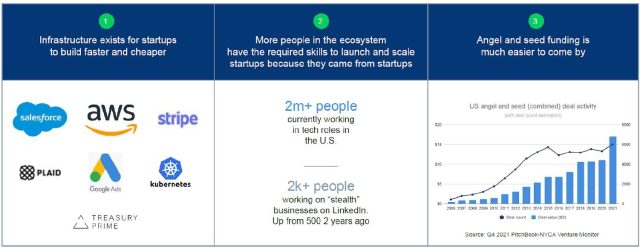

And there are certainly opportunities for resilient founders and companies in a market correction. As with prior downturns, we believe there is a correlation between economic cycles and the formation of category-defining companies. Companies such as Uber, Airbnb, Square, WhatsApp, MailChimp, and Adobe were all founded during recessionary periods. Moreover, today’s founders have an arsenal of tools ready for them to launch their disruptive companies in a cloud-based world with less capital required for growth and the ability to operate with no hard assets. And venture capitalists are still hunting for startups that could well become tomorrow’s category-defining companies.

A great example is Deliveree. Genesis visited Deliveree at its South Jakarta office in June to catch-up with Tom Kim, Deliveree’s Chief Executive. Tom was wrapping up Deliveree’s Series C fund raise and shared how Deliveree had been keeping a tight rein on hiring and marketing expenses which is why the company was able to garner an industry-leading gross margin in the mid-teens, compared to better-funded competitors, some of whom have low, single-digit to negative gross margins.

Brisk Pace of M&A Transactions

A “buyer’s market” has emerged as deep-pocketed acquirers pick up targets of good value. Acquiring targets in order to bulk up seems to be more attractive as the IPO window remains closed, keeping exit valuations depressed.

For example, India’s Pine Labs acquired Southeast Asian startup Fave for up to $45 million. Singapore’s Funding Societies announced it is acquiring digital payment provider Cardup to expand its payments offering.

In fact, Genesis has been receiving requests from founders who want to strengthen their balance sheet with venture debt for the sole purpose of acquisitions – a smart way to raise lower dilutive capital and add breadth and depth to their business.

We expect the pace of M&As to gather further in coming quarters given the conversations we have been having with founders who want to leverage on venture debt to buy up smaller competitors.

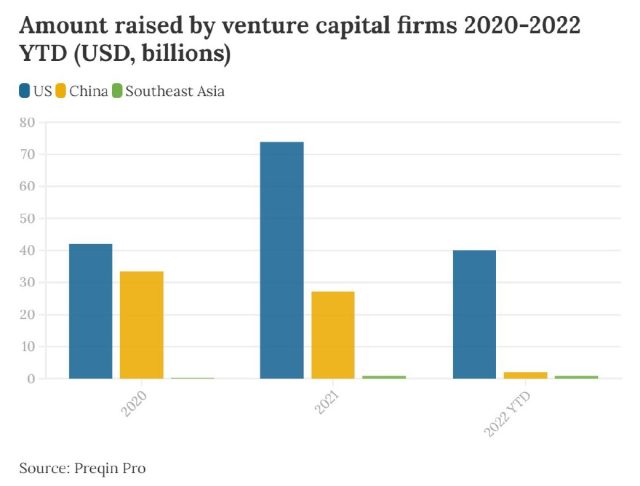

Abundant Dry Powder Globally For Venture Capital Investments

Preqin estimates there is more than $497 billion of global venture capital dry powder as at May 2022 (dry powder being the amount of capital that has been committed to funds minus the amount that has been called by general partners for investments).

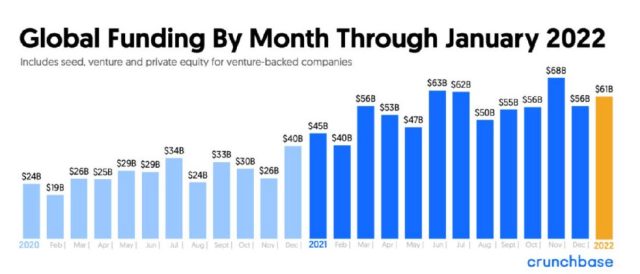

Quarterly funding levels in 2022 remain above quarterly funding levels in 2020 and prior, according to CB Insights (July 2022) with $108.5 billion raised across 7,651 deals. This is despite the fact that quarterly funding has slowed in 2022 amidst tightening liquidity and a global meltdown in technology stocks.

US VC fundraising tops $120 billion for the second consecutive year, according to Pitchbook. A strong showing from established managers in the first half of the year has pushed capital raised to a record pace. These managers have closed 203 funds worth $94.7 billion through the first six months of the year. Already, 30 funds have closed on at least $1 billion in commitments, eight more than the previous full-year high of 22 recorded last year. While this activity is most likely a continuation of momentum from 2021, it’s still an encouraging sign around the level of capital availability through the uncertainty that the next few years may bring.

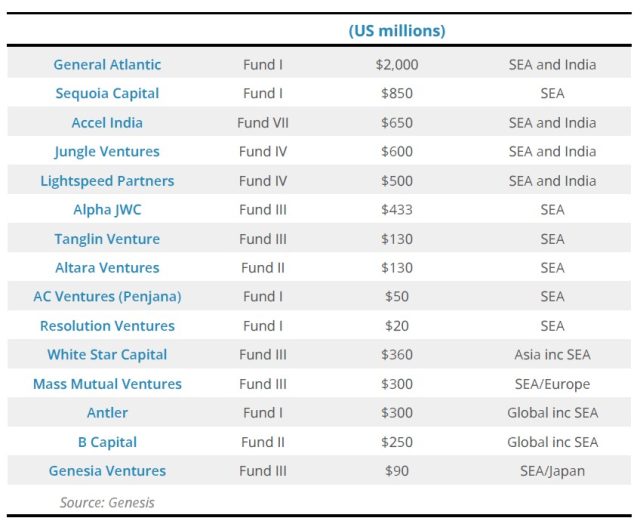

In Southeast Asia, fund investors have increased allocations to the Southeast Asia venture corridor. Southeast Asia and India-focused VC funds have raised $3.1 billion in the first 5 months of 2022, eclipsing the $3.5 billion these funds raised in all of 2021, according to a Nikkei Asia report in May 2022.

Established Southeast Asia players like Sequoia, Accel, Jungle and Mass Mutual have raised larger, multi-stage funds. Sequoia raised $2.85 billion, which includes its first dedicated fund for Southeast Asia with a pool of $850 million. And despite the shaky short-term outlook in tech, Sequoia remains optimistic about Southeast Asia’s start-ups, as do new entrants White Star, Antler, and Altara. From our conversations within our network of General Partners (GPs), it is evident that companies that can demonstrate financial discipline and prioritise healthy topline growth with manageable bottom-line expenses will be rewarded in this investment climate.

While GPs believe that the pace of investment may slow compared to 2021, this does not also mean that investing into new deals will come to a halt; rather the deal selection and diligence process will take longer as GPs will now insist on observing certain metrics and may choose to sit on the sidelines while monitoring progress.

On the topic of valuation, we also notice that GPs have already lowered their WTP (willingness to pay) and this is a common theme across funds globally. Seed and pre-A startups are likely most impacted and may see as much as 50 – 75% reduction in valuation as investors prefer not to take very early-stage risk. Series B, C and D startups remain attractive for GPs to continue investing in given their life-cycle and more reasonable enterprise values, and as highlighted above, there remains a barrage of early growth startups that have raised $50-200 million in a single round of financing with little to no discount to valuations. It also appears that funding has shifted away from late-stage pre-IPO mega deals which has resulted in the declining minting of new unicorns into the tech sector (which mirrors the global phenomenon).

Summary

While we recognise this will be a tough period for investors and companies alike, we equally believe that this will be a rewarding time for investors and GPs who have stuck to their investment thesis of backing mission-driven founders who are building sustainable businesses and aiming for market leadership positions.

The medium to long-term outlook of venture capital investing will improve as valuations and investment pacing return to more sustainable levels. And not forgetting the abundant VC dry powder waiting to pounce on attractive deals in the shorter term.

All of this should also lead to more robust dealflow for venture lenders like Genesis. Investors are now more focused on more sustainable companies with a path to profitability, healthy gross margins, lower burn, more reasonable valuation ascents etc. These are the very companies that Genesis has always invested in. In fact, in the last 2 quarters, Genesis reviewed more than $100 million of deals, and since inception, our total dealflow has crossed the $1 billion mark, which is a significant milestone.